Breaking the Cube: A Perspective on Women, Life, Freedom

Written by Tachiya Bryant

“Cube is not geometric for me. A cube is religious. A cube is political.”

-Pantea Karimi

Freedom of speech is a right we all have. The mediums we use to express it are up to us. Pantea is an example that the pen is mightier than the sword–or in Karimi’s case, a pair of shears. Pantea Karimi is one of many who have spearheaded a viral movement called #womenlifefreedom, in response to the Iranian women’s liberation protests which has generated over 2 million Instagram videos and countless hashtags. These videos show women cutting off their hair in solidarity with Iranian women. The #womenlifefreedom movement has generated impressive traction across social media, but the virality has not diluted the message. Pantea has managed to keep the #womenlifefreedom movement intact and expand its borders to a global spectrum. She has humbly agreed to sit and give us insight into her perception of race, her identity, and her use of art to express those thoughts.

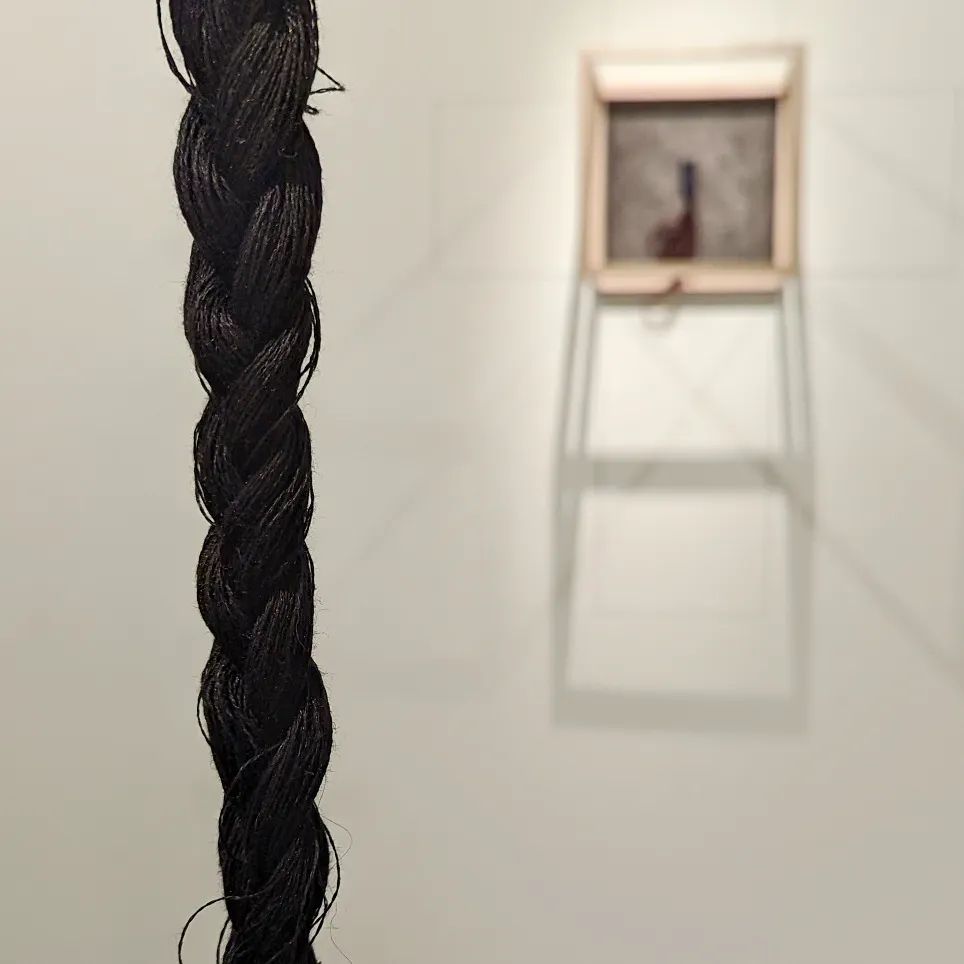

Pantea stopped by the Institute of Contemporary Art San Jose to see Mildred Howard’s exhibit. Inspired by her work, we began to have a conversation about her latest exhibition. Aside from Pantea Karimi’s full-time job teaching, her art is in high demand. She gushed over her new exhibition, “cube is NOT geometric” which is on display at the Mercury 20 Gallery until November 26th. She opened up about the cube is NOT geometric and the September protest that evoked an urge to create her latest works. She says:

“All these years being outside Iran, I thought I had escaped the coercive force of compulsion, but the death of Mahsa Amini took me back to the first time I had to wear the mandatory hijab at school and other public places in Iran when I was a small child. The upheaval and the flashback took me to a very dark, emotional place. As a female artist who also had firsthand experiences with the morality police, I was compelled to respond and extend the exhibition’s content.”

Run-ins with the morality police are not only anxiety-provoking but can be life-threatening for women. Pantea’s visit to Iran in 2016, almost prevented her from leaving the country. Pantea wore clothing to the airport the morality police deemed “Too tight” and was kept in a room and questioned for more than 30 minutes. The female officer refused to release Pantea despite her superior’s orders. After a shouting match, the officer decided to follow directions and release her. She has not been back to Iran since.

Karimi’s latest exhibition is not the first acknowledgment of Iran’s current events. Naked Cube was a dedication to Iranian women, girls, and her cousin, Sadaf attacked by the morality police in Shiraz, Iran October 9th. On October 6th, Pantea Karimi sporadically filmed her friend cutting her hair and donating it for her artwork. The video organically grew across multiple platforms and has reportedly generated 2 million views. The message has superseded the borders of Iran, despite the government shutting the internet down. In hopes of silencing protesters, it seems the power play has only brought Iran more attention. Protestors are fighting for change even if it means being jailed or a final consequence. MSN has reported,” The women-led protests persist despite the bloody government crackdown that has killed more than 300 people, including 41 minors, according to estimates from Oslo-based Iran Human Rights organization.”

The complexity of being a woman of color is difficult enough without the responsibility of a movement on her shoulders. Karimi has shown grace and personal power while being the face of the trend. No good deed goes unpunished. While the vast majority has rallied around #womenlifefreedom there has been some pushback for the movement. Karimi reflects:

“I did not choose to make a political stance; the political reality forced my hand. Even as an artist, making a stance is not cost-free; I have received threatening messages from several sources. In retrospect, what I experience is a minor inconvenience compared to the existential challenges girls and women face in Iran.”

After a while, these messages completely stopped. Karimi credits others for her inspiration, but her brilliance is all hers. Karimi holds two master’s degrees in graphic design and a printmaking and fine arts degree. Pantea uses her education and love of art to express her artistry. The mastery of both seeps into every piece she has produced, and it shows.

Personal identity is a common theme in Karimi’s work. Being an Iranian American, her relationship with America and her traditional culture has been complicated since arriving. She says:

“As an Iranian-born immigrant, the concept of race has been a perplexing construct to me; the federal government considers Iranians as white, but that is not the reality of my experience living in America.”

It opened up a deeper conversation about racial identity in white spaces. Karimi is an Iranian American. Her culture defines her art, morale, and perception of the world. To reduce her racial label as white is something Karimi will not stand for. She often checks “OTHER” and writes “Iranian American” on forms that require her to identify her race. Something as simple as checking a box to the Eurocentric eye means erasure for many cultures like Pantea’s. Inclusivity doesn’t stop with showing solidarity for countries in a global crisis. It means adopting and holding spaces for those people as well.

Pantea embraces her Iranian roots but lives her life from a fresh modern perspective. I asked her if she felt there was a way to keep traditional values in Iran while embracing the new direction Iranian women are fighting for. She states:

“Iran is a complex society with a long history and equally long memory. If I may self-stereotype, by and large, most Iranians are modern, secular, and willing to both adapt to new ideas and adopt new ways to survive. Close to 70% of higher education students are women and these women are increasingly asserting themselves in a competitive world. These confident women cannot be contained, subjugated, or marginalized under the rule of gender apartheid while recognizing and appreciating their country’s history. Blending the desire for modernity while respecting and using tradition is another achievement modern Iran woman has attained.”

This doesn’t mean that change can happen at once. Many countries have been governed under these principles for decades. Gradually, we see many countries embracing things outside of societal norms. Pantea recalls the last time she visited there was secular music being played in a cyber cafe. Which wasn’t surprising to the baristas, but had Karimi stunned. Adopting modern ways of living to improve women’s lives shouldn’t be seen as taboo. Women deserve to experience life outside of laws made under the guise of religion.

Beyond racial identification, Pantea won’t reduce herself to a race or gender. She rebels against the boxes society places her in. Pantea Karimi creates the boxes and smashes them for art. The rebellious spirit Pantea holds is inspiring. Aside from her admirable spirit, her work ethic should also be highlighted. She is currently working on a new exhibition in between her courses. We asked for an exclusive on her new pieces. She laughs

“I get my geometric side from my father and my botanical side from my mother. I think it’s my mother’s turn to be shown.”

The complexity in Pantea Karimi’s artistry is forever encapsulated in her pieces even when her collapsible exhibition is done. Her talent and brilliance exceed any credit she would give herself. You can see cube is NOT geometric at Mercury 20 in Oakland until November 26th.