A Post about David Pace

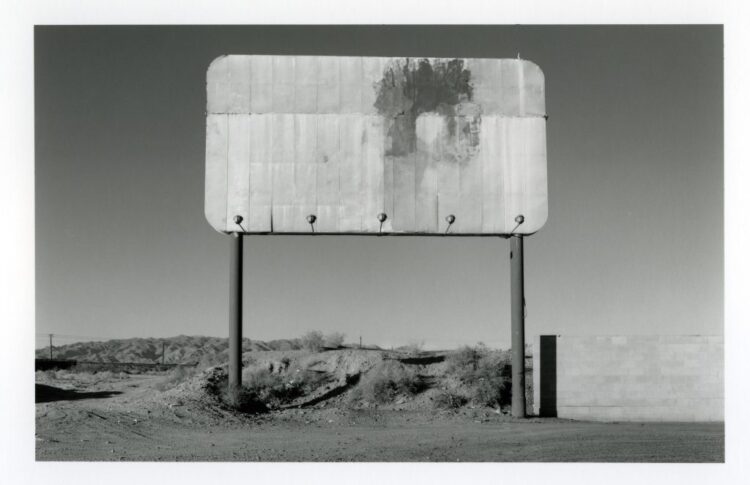

David Pace, Route 66, 1989, photograph. Collection of Diane Jonte-Pace.

Written by James G. Leventhal

When I think of David Pace, I see him winking at me, with a knowing look. “Knowing” is a word I think a lot of David’s friends, colleagues, and loved ones would use about him. And with his wink, he could help to imbue confidence. He saw the gifts of others as important. I have very much had David in-mind recently. Below are a series of recent thoughts, recollections, and ways in which David came up for me. He had an aura of the love of others; so often manifested in his lifelong partnership with Diane, which is well documented, in their collaborative book Where the Time Goes (2020).

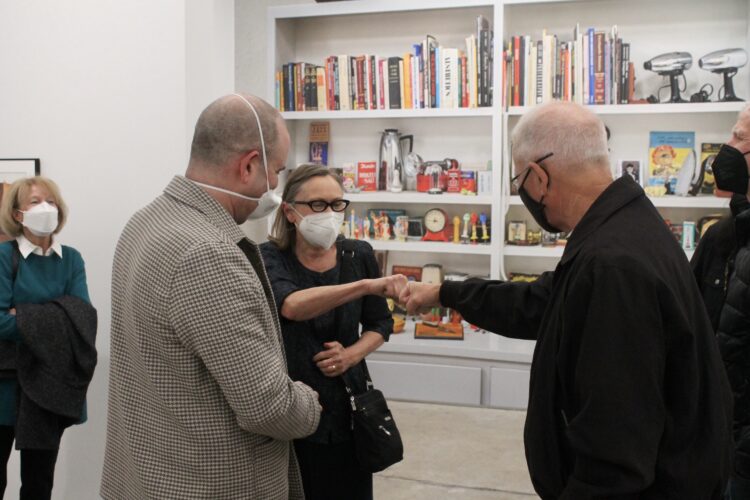

David was a photographer, a father, and an institution builder. The ICA San José (SJICA) is one of his greatest legacies in my mind. I’m prejudiced, now as the director of the SJICA. At the ICA San José, David was generous with his thinking and guidance. He was financially supportive as well. With his passing in 2020, the back gallery of the ICA San José is now named in tribute to David. Since we dedicated the gallery in 2022, we have been showing a series of installations that we feel would resonate with David, both for their commitment to present world issues, and for their use of various mediums, especially photography or film.

The first installations showcased David’s work itself entitled Speaking with Images, including short films he had developed. The second was Facing West Shadows, then Adrian Burrell, and now SJSU professor Rhonda Holberton. David also helped to lead the curatorial committee that worked with staff in the past. I get the sense that he would have just loved sitting in on meetings to discuss these exhibitions, and what’s to come.

David was someone who had a larger-than-one-life legacy across many organizations and even continents. A keen reminder of this was his recent posthumous exhibition at Blue Sky, Oregon Center for Photographic Arts in Portland that focused on David’s photographic work in West Africa.

In 2019, shortly before his death, David described his vision for the architectural project: “I am committed to communicating the beauty of these spaces, so clearly marked with the traces of human life and labor, and to portraying the realities of life in West Africa” (Personal Structures: Identities, p. 394).

I am struck by how this same message has been championed by world-class architect David Adjaye. Adjaye is most well known in the U.S. for having designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He also regularly shares the architectural legacies of Africa on Instagram, so much overlooked previously in our global, institutional aesthetics. David knew.

A foundational embrace of the life of Africans was important to David, and he made a lot of deep friendships there, including his friend, the Burkinabe photographer Warren Saré, who said “To be a photographer is to be a witness to one’s time.” David epitomized that and helped support his friends, such as Saré and their work, such as Saré’s Anciens combattants.

Now, I’ve joined Blue Sky’s mailing list and I was thrilled to see that the next exhibition showcased Bay Area photographer Sam Geballe, with a program in-conversation with Brittney Cathey-Adams. I got to know Cathey-Adams work, because they had been a Forecast winner at SFCamerawork in 2020 when I was involved at SFCamerawork, ANOTHER organization that David played a key role in across the decades. Cathay-Adams and Geballe both explore issues of identity, body image, and valuing the self. Looking into all of this, again, I felt like David was guiding me.

Pictured: Ancien Village, Back Street by David Pace 2012. Courtesy of Diane Jonte-Pace, and Blue Sky Gallery

While I was looking for David Pace videos online, I also found this video from 15 years ago done by then curator at the San Jose Museum of Art Joanne Northrup talking about David’s work with taxonomies, including toys and robots: https://youtu.be/FjUIPgiDHcU. Northrup was just recently named to run the amazing Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, just outside Kansas City: https://www.nermanmuseum.org/about/joanne-northrup.html. It’s important to be able to see the connections that persist from David’s time, and how San José has been an important training ground for a lot of art professionals.

The other day, I was visiting with a couple in Los Gatos when I came across one of David’s photographs from the Images in Transition series developed working with Steven Wirtz. Developed from enlargements from wire images, these pictures allow us to explore history, surveillance, and memory.

David Pace and Stephen Wirtz manipulate and transform wirephotos transmitted during World War II. Beginning with an extensive collection of originals assembled by Wirtz over a period of many years, they scan the images, radically re-cropping and dramatically enlarging portions of the archival wirephotos. Their croppings and enlargements expose the artifacts of the wirephoto technology – the dots, lines, irregularities and retouchings from the war years. But the transformations introduced by Pace and Wirtz not only extend, but also reverse, the intentions of the wartime retouchers: Instead of obscuring the dots and lines to create a clearer image, Pace and Wirtz reveal and enhance the dots and lines, exposing the technological processes that produced the images.

The image Libyan Prisoners, January 22, 1942 begs all kinds of questions about who was in control. If it was 1942, were the Germans taking prisoners? Or were these prisoners taken by Allied forces? Once you look back on war, important questions are raised about who was in power, and who was being controlled and why? More also, when I went back to the publication the introductory essay was written by Matt Murrman, a photo editor I came to know also through SF Camerawork, as he was on the Board when I was working with SF Camerawork. Again, I felt like David was looking over my shoulder, or winking from across the room.